In his 1977 play Abigail’s Party, writer-director Mike Leigh takes you into the details of an out-of-town dinner party in detail so mundane and tedious that when something truly dramatic happens, a fatal heart attack, you gasp. daze. . The stakes were so low and so high that the game began to feel like your own uneventful life. And now something absolutely amazing has happened. And it hits you accordingly. Our General Review find a similar situation in the latest version of Obsidian.

If Mike Lee was the master of kitchen sink drama, then consider Obsidian the purveyor of detective detective. It’s a murder mystery told somewhere between the footsteps of a person and the movement of tectonic plates, a story that doesn’t bother to entertain you as long as you understand the exact details of German village life in the 16th century. and his attitude toward the church.

Therefore, it takes quite a while before any murders take place. Or rather a secret. Instead, the first few hours of the Pentimento are spent adjusting to existence in the Holy Roman Empire. The hero Andreas stayed with some farmers in a village near the abbey, where he was commissioned to create an illustration for the text. In my game, he’s a skilled speaker of Italian descent with hedonistic tendencies, a logical mindset, and half medical training. In yours, he will have a completely different backstory and related abilities based on your decisions. It’s not Wildermyth, but there is at least some player input into the opening hours, which are otherwise pretty linear.

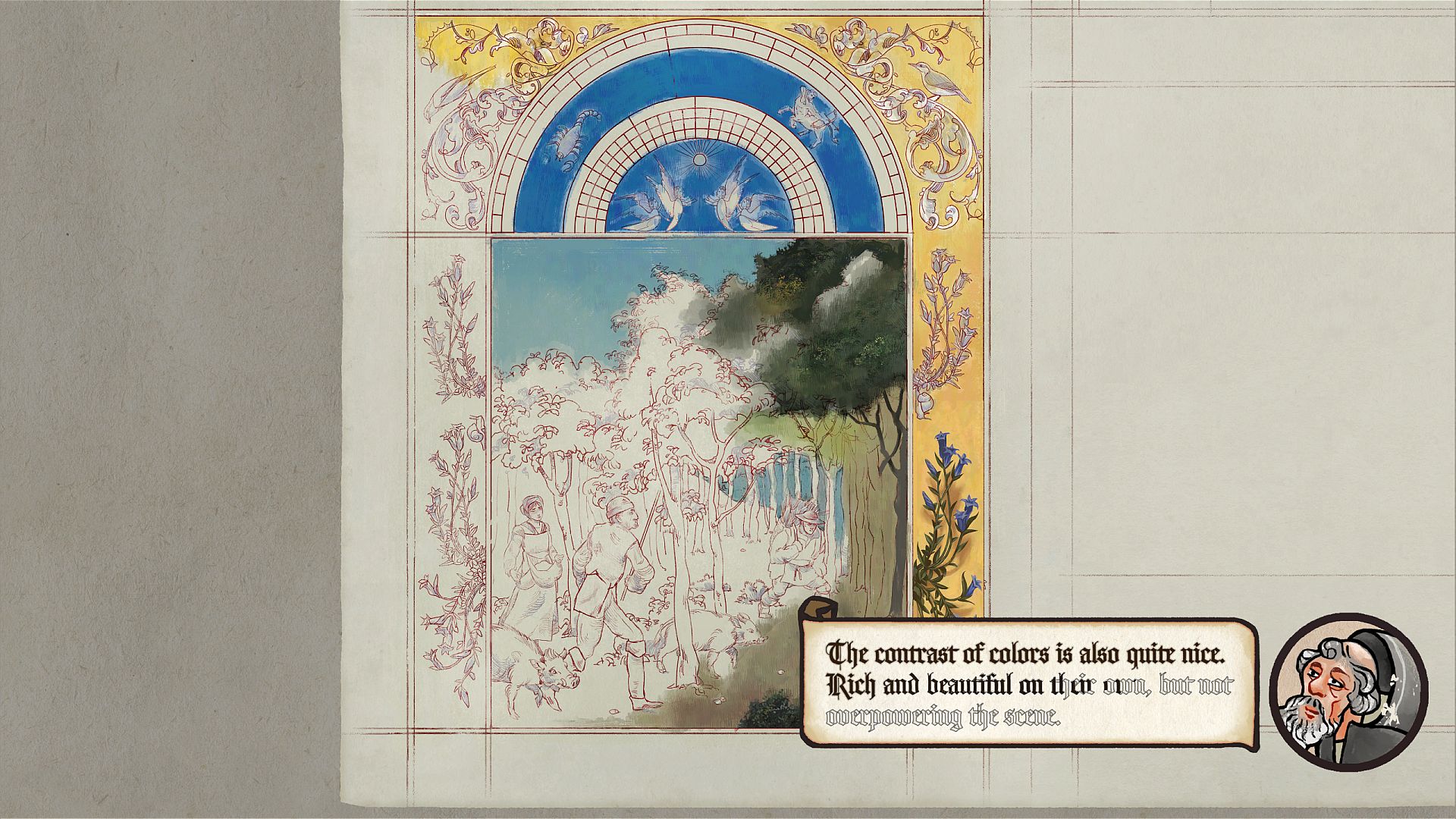

The presentation is amazing. This is Kingdom Come: Deliverance rendered in 2D point and click. It is an interactive novel, with calligraphy written as you experience it, with pen strokes suggesting tone of voice, social position, time, and place. By the end, you’ll be pretty tired of the sound of pen on paper, but fonts have never worked so hard to convey character and class. The art style is somewhere between a medieval tapestry and a webcomic, and the UI conceit is that you see everything like the pages of a book.

As you progress from screen to screen through your village, a space librarian turns the page and a new scene appears. Certain names and lies are soulful in the dialogue, and those who click dessus, you are accueilli avec a doigt d’une longueur alarmante pointant vers ce mot, then the camera zooms in on the page, a petite definition of glossaire dans the margin. Your map and journal live in the same book, and while that makes navigation a bit awkward, they are at least thematically consistent.

There’s something fascinating and even poignant about the Persona-style daily schedule. Getting used to the pace of life in 16th century Bavaria really anchors you in the town of Tassing. It feels like living a real life there, waking up on Gernther’s farm, heading to the abbey scriptorium to work on your art, stopping for lunch at a few places, heading back to work, then heading back via the abbey pre to the village. around sunset and make other social calls before night and before bed. It’s a routine that will teach you a bit of history and fill you in with a little extra immersion all at the same time. Unlike Persona, though, time only advances once you’ve completed certain actions, so it’s not so much a question of figuring out how to spend your time, but rather figuring out which field (or fields) you should be looking at to start the game. next leg of the day. .

Meal time is very important here. They are an integral part of your daily schedule, and you can usually break bread with one of the many households in the village. Sometimes not much comes out, except a bit of history and friendship. Other times you can get important information from your fresh stew and quail.

But above all you work. In the first act, Andreas works in the abbey’s scriptorium, where monks illustrate religious works commissioned by high officials and nobles of the Church. We are only a few decades away from the invention of the printing press at the beginning of history, and Pentiment shows you how important these innovations are in our society. Under certain circumstances, they can even become a matter of life and death.

And in the end they do. Like Abigail’s feast, the moment the blood is spilled, it feels even more incredible because everything you’ve been through has been so normal. You fight in the scriptorium over the speed of Brother Pietro’s work. Dinners on the farm, rye bread and sheep cheese, and gossip from the nuns. Heavy rain and damaged wall. So: murder.

Only then do you have a meaningful contribution to Pentiment. In this first murder investigation, your actions and decisions begin to carry obvious weight. You run through town like a robed Columbo, picking up clues, untangling gossip from important facts. And what you find, or don’t find, will really affect the completion of the case when the Archdeacon and his people arrive in town. Ultimately, it is a matter of life and death.

It’s a repeating pattern in Andreas’s life, told alternately in microscopic detail through his daily routine and in huge leaps through time, after which it’s up to you, the player, to find out what Andreas has been up to in the meantime through of conversations. currently. He is a true renaissance man. An artist, yes, a hedonist and a storyteller, perhaps also an amateur detective.

Payments, if that’s the right word, given the dark theme, comes to an end in his murder investigation. It is here that all of your decisions, the information you have gathered and how you have interpreted it, sends the story in one of several directions and as time ticks by at breakneck pace, you are shown the consequences of everything you have said. . . and do.

So mechanically and systemically, regret is pretty impenetrable. The crime investigation elements aren’t strong enough to rival BigBen’s Sherlock Holmes games, but they’re a way to round out the seismic narrative. His conversations are replete with historical research and political opinions, to the point that he could probably present an unconvincing position on real-world Lutheranism, if it ever came up.

But what bothers me is the pace. Is it a deliberate design philosophy to slow travel to the point where the player soaks up every bit of historical accuracy, realizing that the typeface each character “speaks” in reflects their social standing? Or, and I guess you could say I suspect it, is it an accidental byproduct of a well-intentioned but clunky picture book presentation?

At one point, you have to collect sticks for the local widow, and the way Andreas bends down to pick them up is like Pentimento paid by the hour. Everything you do seems to take longer than you expected, whether it’s going through the tons of scenarios involved in each conversation or navigating from one part of town to another.

The point is that humans are programmed to invest more emotions when we invest more time. The stories we spend a lot of time with seem to be inherently more epic, whether or not we’re impressed by particular events. As the disillusioned Hungarian director Béla Tarr puts it: “I despise stories because they mislead people into believing that something has happened. In fact, nothing happens when you run from one state to another… Only time remains. It is perhaps the only thing that still remains real: time itself; years, days, hours, minutes and seconds.

In terms of story and murder mystery, Pentiment is essentially a game about time. The ambitions and dreams you had when you were young and how easily they can be frustrated. Your relationships and their fragility. How the family environment can drastically change due to the most random events. In the end, no matter which character you choose or what choice you make, no matter how boring the clunky pacing is… you end up complaining about wasted time, wishing you could go back and do things differently.

For much of my time with him, I wondered if he would have given Pentiment the benefit of the doubt on this point if Obsidian hadn’t. The answer is that he probably wouldn’t and, ironically, I probably would have given up just before the legendary studio RPG’s qualities really came to the fore. In truth, the art style is not flashy in that I find it particularly enjoyable, but the craftsmanship demonstrated by the way it immerses you in the concerns and motivations of a small group of villagers, nobles, and dignitaries. Biblical scholars are an obsidian classic. .

The writing can be inconsistent in tone, from formal Old English conventions to very modern American parlance like “I think I could learn this” or “Rain doesn’t work that way,” so the dialogue itself isn’t as Watch out. like the typography that represents it, but in terms of going from A to B to C, you can feel the experience and craftsmanship.

It’s hard to imagine this game being so authoritative in its historical details if it was created by another developer. I don’t know anything about 16th century Europe, but I believe what Obsidian tells me.

Don’t expect a second to speed up like The Outer Worlds or The Stick of Truth. Or even the pillars of eternity. But if you’re not in too much of a hurry, here’s a distinctive slice of the story that unfolds in life in the 16th century, hour after hour, meal after meal, and also somehow slips into the giant timeline of aftermath. for the player. And was Mike Lee successful?

General Review

A clumsy historical murder mystery that pays little attention to suspense or pacing, but is so packed with detail that you can’t help but respect it. Pentiment plunges you into 16th century Bavaria and is a real highlight.

Source : PC Gamesn